In Unit 5 of Math we have reviewed place value with very large numbers. Children should now be able to read, write and compare numbers to the millions. (Compare, in this context, means to tell which numbers are greater or less than each other, and also order numbers from smallest to largest or largest to smallest.)

Now we have turned our attention to very small numbers. The question to the class yesterday was:

What is less than one, but larger than zero?

Initially, this question caused some confusion. Some children thought the question was impossible to answer. Other children thought the answer was “negative numbers”. When I phrased the question a different way “What is less than one dollar? What is less than one meter?” I had answers such as “10 cents”, “a decimeter” or “a centimeter”. This helped students to realize it is possible to have less than one whole, and still have something.

Although we are just beginning our exploration of decimals and fractions, you can help your child with these more abstract numbers by identifying whole objects around your house and discussing how they can be broken down into smaller equal parts. Decimal numbers represent amounts less than one. When anything is broken into ten equal parts, it results in tenths (for example: a dollar can be split it into ten dimes. A dime is a tenth of a dollar). When a tenth is broken into ten equal parts, it results in hundredths (a dime can be split into ten pennies. A penny is one hundredth of a dollar).

Examples could include:

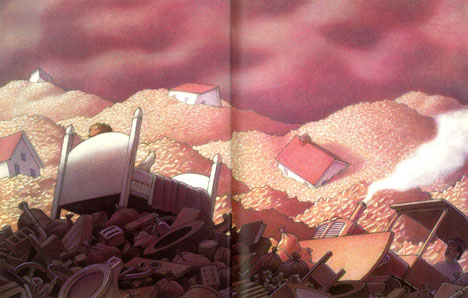

– a chocolate bar can be broken down into ten equal pieces

– a piece of paper can be broken down into tenths and hundredths

– a litter of water or milk can be split into tenths or hundredths

– pizza, pie or cake can be split into tenths